A few individuals have been cured of HIV, but scientists are working on developing treatments that will be available to more people affected by the virus.

Over the past twenty years, HIV infection (the virus that causes AIDS) has been treated through aggressive medical procedures in a handful of individuals. Several others have also received this treatment and appear to be free of HIV, but it is too soon to declare them definitively cured. Currently, their status is considered long-term remission, but they are considered potential treatment cases. All of these patients received stem cell transplants, using cells collected from adult donors’ bone marrow or cord blood.

According to LiveScience, scientists announced the first definitive HIV cure in 2008, and since then, two more definitive cures and two potential cures have been reported. The latest reports of such cases (one definitive cure and one potential cure) were announced in early 2023.

With increasing knowledge, these treatments may become more common in the coming years. Although, currently, these treatments are risky and largely inaccessible to the tens of millions of people worldwide who are HIV-positive.

HIV drugs, known as antiretroviral therapies (ART), can increase the lifespan of HIV-positive individuals and significantly reduce the risk of virus transmission. However, these drugs must be taken daily throughout one’s life, can interact with other drugs, and come with some risk of serious side effects. Therefore, scientists hope that these definitive treatment cases will pave the way for developing new and more accessible treatment strategies.

What treatments can cure HIV definitively?

All individuals who have been definitively cured of HIV have been treated with stem cell transplants. All of these patients were not only HIV positive but also had a type of cancer (acute myeloid leukemia or Hodgkin’s lymphoma). These cancers affect white blood cells, which are a key component of the immune system. These types of cancers can be treated with stem cell transplants.

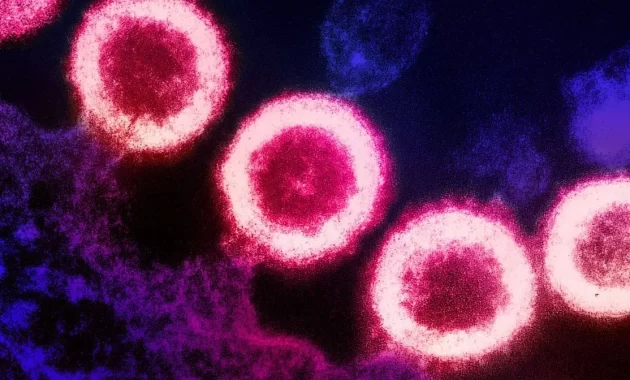

Doctors collected stem cells from individuals who had two copies of a rare genetic mutation (CCR5 delta 32) in order to simultaneously treat cancer and HIV. This mutation inactivates a protein called CCR5 on the surface of cells. Many strains of HIV use this protein to enter cells.

The virus starts its work by attaching to another surface protein and changing shape, then it connects to CCR5 to penetrate the cell. Without CCR5, the virus cannot enter the cell. (According to a review published in the journal Frontiers in Immunology in 2021, some less common strains of HIV use a different surface protein called CXCR4, and some strains can use both. Therefore, before transplantation, patients were screened to ensure that most or all of the viruses present in their bodies use CCR5.)

To prepare for transplantation, patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy are subjected to an attack so that T cells (a type of immune cell) that are cancerous and vulnerable to HIV in their bodies are destroyed. This weakens the patients’ immune systems until the transplanted stem cells can produce new, HIV-resistant immune cells. Patients take immune system-suppressing drugs for a period of time after transplantation to avoid graft versus host disease (GVHD). In GVHD, immune cells from the donor attack the host’s body.

Most patients have received stem cells taken from adult bone marrow donors. These cells must have high compatibility, meaning that both the donor and recipient must have special proteins called HLA in their body tissues. HLA incompatibility can lead to a catastrophic immune reaction.

One of the patients (the first woman to receive a stem cell transplant and who has been in remission for a long time) received stem cells from cord blood donated at birth. These immature cells are more easily compatible with the recipient’s body, so only a little compatibility is needed. She also received stem cells from one of her adult relatives to help strengthen her immune system during the time when cord blood cells increase.

Since cord blood stem cells do not require complete matching and are a more convenient source than bone marrow, such transplants can be offered to more patients in the future. However, according to Dr. Evan Bryson, director of the Los Angeles-Brazil AIDS Consortium at the University of California and one of the physicians involved in the treatment of this patient, more research is needed to confirm the effectiveness and safety of this type of transplantation.

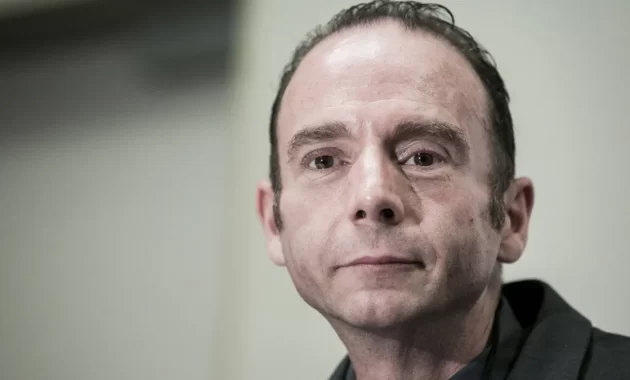

Who was the first person to be cured of HIV infection?

The first person to be cured of HIV infection and initially referred to as the “Berlin Patient” was treated in Berlin, Germany. He revealed his identity in 2010.

Timothy Ray Brown, an American studying in Berlin, was diagnosed with HIV in 1995 and began taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) to reduce the amount of HIV virus in his body. In 2006, Brown was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia and in 2007 underwent radiation therapy and a bone marrow transplant to treat the disease. Brown’s doctor saw this situation as an opportunity to simultaneously treat his patient’s leukemia and HIV.

Brown had been cured of HIV after undergoing radiation therapy and receiving an HIV-free bone marrow transplant, but his cancer returned and he required a second transplant in 2008. In that year, researchers announced that the Berlin Patient was the first person to be cured of HIV. Brown remained HIV-free for the rest of his life, but he passed away in 2020 at the age of 54 after a recurrence of leukemia and cancer that had spread to his spine and brain.

How many people have been cured of HIV so far?

As of March 2023, three people have been cured of HIV and two others are in long-term remission. In addition to Timothy Ray Brown, the cured individuals include the London Patient (Adam Castillejo) and the Dusseldorf Patient (whose name has not been disclosed). Two possible cases of cure include the Berlin Patient and the New York Patient, who is the first woman to receive the treatment.

Dr. Deborah Persaud, who monitored the New York Patient and is the interim director of pediatric infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, said during a March 2023 press conference that currently there is no official distinction between HIV cure and long-term remission.

Dr. Steven Deeks, an HIV specialist and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who did not participate in the treatment of any of the patients, said: “The Dusseldorf Patient was likely the second person to be cured, but the medical team was cautious and stopped antiretroviral therapy after several years and waited a long time before concluding that he was cured.”

The patient from Dusseldorf was treated in 2013 and continued to take ART drugs for about six years. They have now been off medication for over four years. Meanwhile, Kastihou received a transplant in 2016, stopped ART treatments just over a year later, and in 2020, their treatment was confirmed before the Dusseldorf patient.

What can be learned from cases of HIV treatment?

Cases of successfully treated HIV provide information on how the body changes after treatment and offer insights into future strategies for HIV treatment.

Scientists have found that even after treatment, highly sensitive tests show scattered traces of HIV DNA and RNA in the body. However, according to Dr. Björn-Erik Ole Jensen, a senior physician at the University Hospital of Dusseldorf who conducted comprehensive tests on the viral remnants of the Dusseldorf patient, these remnants are unable to replicate. He told Live Science that none of these viral traces have the ability to replicate. Other physicians involved in similar cases of treatment have conducted similar tests and have come to the same conclusion.

According to Jensen, changes to the immune system may be a better indicator of the success of a transplant. About two years after the transplant, the Dusseldorf patient had immune cells that reacted to proteins associated with HIV, indicating that these cells had been exposed to the virus and stored a memory of it. Jensen said, “But over time, these responses disappeared until the HIV reservoir reached zero. The change in immune activity was a convincing sign that the Dusseldorf patient could stop taking ART.”

Are scientists currently conducting research to find alternative methods to treat HIV?

According to Johnson, scientists are working on alternative treatments that can bring about the same changes in the body without relying on donor stem cells. By avoiding stem cell transplants, future treatments may eliminate the need for aggressive chemotherapy and radiation therapy, as well as the use of immune system-suppressing drugs and the risk of GVHD.

Some research groups are developing HIV treatments based on modified cancer treatments, in which some of the patient’s immune cells are taken, the CCR5 receptor is removed, and the cells are made responsive to HIV proteins before being reintroduced into the patient’s body.

Another potential treatment strategy includes gene therapies that edit the body’s DNA to delete the CCR5 coding gene or force cells to produce proteins that inhibit or deactivate CCR5. Some researchers are also working on targeting CXCR4 methods. Dix said, “With the gene editing revolution taking place in other medical fields, it may be possible to do this with just one injection.” Johnson noted that these approaches are still being tested in the laboratory and on animals, so scientists do not yet know how they will work in humans. Nonetheless, she believes there is cause for hope.