Gordon Moore’s inventions helped lay the foundation for the modern world, and it’s no wonder that he is known as one of the most popular and influential figures in Silicon Valley and the chip industry.

Gordon Moore, the co-founder and former chairman of Intel, whom you may know more for “Moore’s Law,” passed away on March 24, 2023, at the age of 94, at his home in Hawaii.

If hundreds of millions of people around the world have access to laptops these days and have everything from digital scales to gaming consoles, smartphones, cars, and jets equipped with microchips, it is due to the efforts of Moore and a handful of his colleagues at Intel, the chip maker based in California that helped usher in the era of “Silicon Valley” and achieved such mastery in the world of technology that industrial giants of the railroad and steel industry had experienced in another era.

Moore’s heart’s desire was to become a teacher, but he couldn’t find a job in that field. He later called himself a “accidental entrepreneur” because his $500 investment in the fledgling microchip business, which transformed the electronics industry into one of the world’s largest industries, turned him into a billionaire, and his wealth was valued at $7.1 billion at the time of his death.

The world of technology is full of exciting predictions that sometimes become a reality. Ada Lovelace, the first programmer in history, predicted in the early 19th century that one day it would be possible to create music and artwork with computers. Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the web, predicted in 1999 that the internet would become a platform for collaborative work and that computers would become more intertwined with people’s daily lives. Steve Jobs also predicted in 2007, when the first iPhone was unveiled, that smartphones would become the most important computer device for many people.

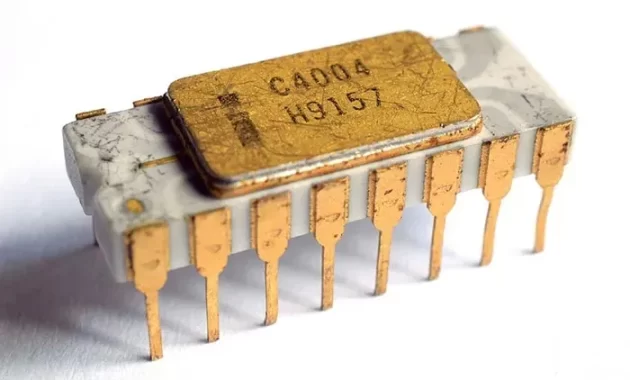

But among these predictions, one was so important that it was referred to as a law, and technology companies based their product strategies on it; yes, I’m referring to Moore’s Law. In 1965, Moore predicted that the number of transistors that could be placed on a silicon chip would double every two years, and thus the processing power of computers would increase exponentially.

Join us to get acquainted with the life and achievements of one of the most popular and influential figures in Silicon Valley, someone whose inventions helped shape the modern world.

Life of Gordon Moore at a Glance

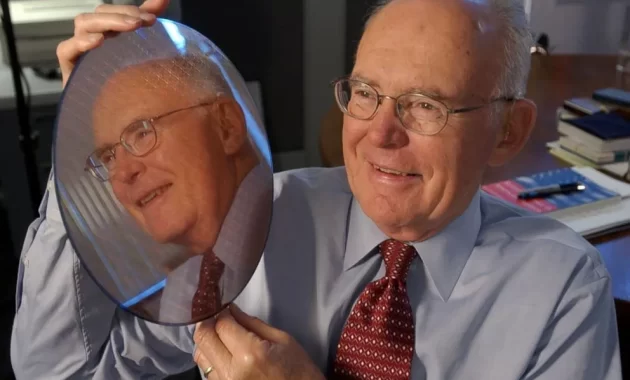

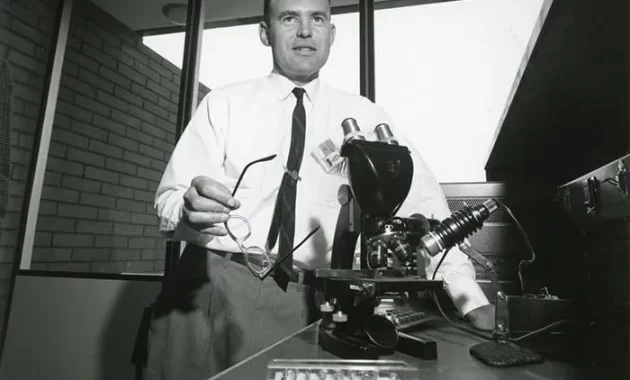

With his humble and friendly demeanor that concealed his brilliant mind, Gordon Earle Moore was one of the most respected and beloved figures in Silicon Valley throughout his life. He was born on January 3, 1929 in a small coastal town called Pescadero in the south of San Francisco, and grew up near Palo Alto in the northern California city of Redwood. His father was a deputy sheriff and his mother’s family ran the town supermarket.

When he was eleven years old, a neighbor child gave him a chemistry set for experiments, and Moore was able to entertain himself for hours with the kit. Moore said, “In those days, interesting things could be found in chemistry sets. For example, you could make dynamite with a small amount of nitroglycerin!” He was upset that the rules and fears of parents eliminated some of the interesting things in these kits, and probably deprived the world of some scientists, because Moore’s recreation with the chemistry set led him to pursue a degree in chemistry in the future.

Moore first attended San Jose State College, where he met Betty Whitaker, a journalism student. They got married in 1950 and had two sons named Kent and Steven. In the same year, Moore completed his undergraduate studies in chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1954, he received his doctorate in chemical engineering from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

If one Saturday morning while leaving the neighborhood hardware store, you ran into Gordon Moore, you would see him in a faded apron, work boots, and wire-framed glasses. You might mistake him for a farmer who had come to buy something from the store for repairing his home pipes or building a swing for his children.

But Moore was an accomplished engineer. Along with his remarkable Ph.D. degree from Caltech, he had several important inventions under his name, and had earned numerous awards and honors during his career in research and work. Moore also had a strange ability to solve technical problems. For example, if a problem seemed to have five or six possible solutions, most engineers would spend a lot of time trying out all the solutions before arriving at the correct one. But for reasons that neither he nor anyone else could explain, Moore would simply choose one of the solutions and, in most cases, arrive at the correct answer on his first attempt.

Moore was famous for spending his lunchtime at the company’s cafeteria, sitting with a group of engineers to find solutions to problems that had been bothering them for months. Moore patiently listened to their questions and proposed solutions that would take only 15 minutes of thinking, which would save the engineers months of work. He also had a great ability to judge people’s personalities and rarely made mistakes. The only thing that could make him angry was people who repeated the same thing over and over again and tested his patience.

One of the first jobs that Moore pursued after graduating from Caltech was a managerial position at Dow Chemical, which is now the largest plastic producer in the world. In 1994, Moore told Engineering & Science magazine, “They sent me to a psychologist to see if I would be suited for a managerial position. The psychologist told me that I didn’t have any technical problems, but I could never be a good manager.”

Moore ended up working at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Then, in search of a way to return to California, he went for a job interview at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, where he was offered a job, but he decided to reject it because “I couldn’t tolerate the ambient temperature in which I would be working.”

In 1956, Moore joined William Shockley, one of the inventors of the transistor, to work at a start-up company called “Fairchild Semiconductor,” which was founded with the goal of making inexpensive silicon transistors.

However, as you will read later, Moore could not survive more than a year at Shockley Semiconductor and decided to join Robert Noyce and six other colleagues to invest $500 each and launch a rival company called “Fairchild Semiconductor” with a $1.3 million investment from Sherman Fairchild. This decision led the company to become a pioneer in the production of integrated circuits, and these eight individuals received the title of “Traitorous Eight” from Shockley.

In 1968, Harold “Hal” V. Mor and Dr. Forrest C. Shockley, who had already tasted the sweet taste of success in entrepreneurship, decided to form their own company with a focus on memory chips. Mor said in an interview in 1994, “Our new business plan just said that we were going to work with silicon and produce interesting products with it.”

Although the business plan for the new company was very vague and unclear, they had no trouble finding $2.5 million (approximately $19 million today) in capital to launch their startup, which was named Intel. With inventions such as RAM and microprocessors for personal computers and servers, Intel laid the foundation for the modern world.

As soon as Mor became very wealthy, he became one of the main faces of humanitarian aid. In 2001, he and his wife founded the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation by donating 175 million Intel shares. In the same year, they donated $600 million to the California Institute of Technology, the largest amount ever donated to a higher education institution up to that time. The foundation’s assets currently exceed $8 billion and have helped students with more than $5 billion since its inception.

But Mor’s name is best known for his law. He not only predicted that as industries transitioned from separate transistors to smaller silicon chips, electronic devices would become much cheaper over time, but his predictions were so reliable over the years that technology companies based their product strategies on the assumption that Moore’s Law is always true.

Arthur Rock, one of the first investors in Intel and a very old friend of Moore, said, “This is Moore’s legacy; not Intel, not the Moore Foundation, but Moore’s Law.”

Moore’s acquaintance with the most hated founders of Silicon Valley and the “Traitorous Eight”

The “Traitorous Eight” refers to a group of scientists and engineers who left Shockley Semiconductor in 1957 and founded another company called Fairchild Semiconductor in direct competition with it. The eight were Gordon Moore, Robert Noyce, Julius Blank, Victor Grinich, Jean Hoerni, Eugene Kleiner, Jay Last, and Sheldon Roberts.

But what was the story behind this “betrayal”?

William Shockley, a member of the legendary group of scientists at Bell Labs and one of the inventors of the transistor in 1947, received the Nobel Prize in Physics for his extensive research on semiconductors and the discovery of the transistor.

Despite not having a genius-level IQ, he was so intelligent that he skipped a grade in high school and then graduated from Caltech and MIT. He was precise, creative, and ambitious, and like a choreographer who can visualize dance moves, he had the ability to visualize quantum theory and how electrons move. His colleagues said he could look at semiconductor materials and see electrons. Although he loved practical jokes and teasing his colleagues, he had no idea how to behave in a friendly way, and the more successful he became, the harder it was for people to get along with him.

Although back then, the Palo Alto neighborhood hosted technology innovators from companies such as HP and large research institutions such as Stanford University, it was Shockley who nowadays replaced fruits with chips in Silicon Valley.

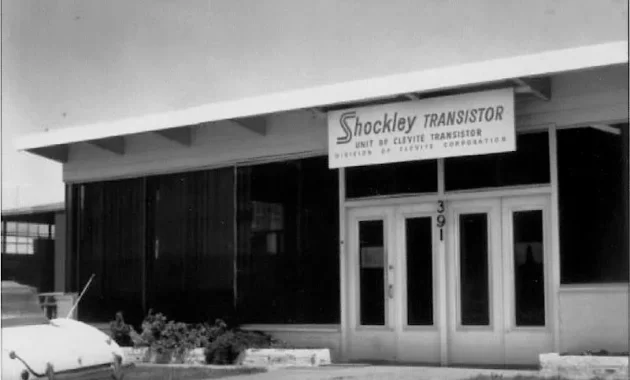

After the invention of the transistor, Shockley was seeking to leave Bell Labs, return to Northern California, and establish his own business in the field of semiconductors. Until in 1956, he brought together a group of specialists to found his company named Shockley Semiconductor, which is now recognized as the birthplace of Silicon Valley, and chemist Gordon Moore joined them.

Shockley’s name was very famous at that time; hence, with a sudden call from him, all the people who were invited to join his company immediately accepted the invitation. Moore said about his employment at Shockley:

“When Shockley was working at Bell Labs, he realized that chemists were heavily involved in his work. For this reason, he thought he needed a chemist for his new operation. He found my name and contacted me. Fortunately, I knew who he was when he called. I quickly picked up the phone and he said, ‘Hi, I’m Shockley.'”

When Moore went to interview with Shockley, he was 27 years old and a year younger than the interviewer. Shockley asked him difficult questions and timed his responses with a stopwatch. Moore answered the questions so well that Shockley invited him to dinner and performed a trick of bending a spoon without using physical force.

Moore specialized in the field of solid-state processes and adding new components and materials to silicon to create electrical properties at Shockley Company. This process, known as doping, is used in the semiconductor industry for doping or adding impurities and is used to make transistors and other semiconductor components.

However, Moore was only able to endure working at Shockley Company for a year because the manager was very strict, ill-tempered, and untrustworthy and did not care about the technical recommendations of his employees about which research area they should focus on.

Shockley’s aggressive behavior, extreme paranoia, and incompetence in management ultimately led to the rebellion of employees against him. There was no one behind this rebellion but Gordon Moore himself; he was the one who planted the idea of separating from Shockley in the minds of his colleagues because he realized that it was not easy to ignore someone who had recently won the Nobel Prize. Especially since Arnold Beckman, the main investor in Shockley Semiconductor, did not want to dismiss him from management in accordance with Moore’s proposal due to his deep friendship with Shockley.

Those days, leaving Shockley Semiconductor to start a new company required a lot of courage

It is important to note that why the decision of these eight people to leave was considered as a kind of betrayal by Shockley. At that time, leaving a well-established company to start a rival company was very unusual and required a lot of courage. According to Regis McKenna, a marketing expert for many technology companies, “the business culture that existed in America at that time was that if you were hired to work in a company, you stayed in that company until you retired. The traditional values of the East Coast and even the Midwest of America were the same.”

Of course, these values no longer apply in America, and it can be said that the eight traitors of Shockley helped a lot to bring about this cultural change. Michael Malone, a Silicon Valley historian, says:

“Nowadays, it is better to leave a company, start your own business, and fail along the way than work in the same company for thirty years. But in the 1950s, this way of thinking did not exist; for those eight people, leaving Shockley to start a rival company was undoubtedly very scary.”

Shockley Semiconductor never returned to normal after the departure of these eight people. Six years later, Shockley completely left his company and joined the board of directors at Stanford University. His paranoia had now intensified, and he believed that blacks were genetically inferior and should not have children.

The brilliant scientist who invented the transistor and brought people like Moore and Noyce to the land of Silicon Valley had now become a hated figure whose every speech was met with ridicule from the audience. On the other hand, the disaster that occurred with the departure of this “eight traitors” group was one of the biggest historical failure.

Fairchild Semiconductor and the Beginning of the Technology Renaissance in Silicon Valley

Initially, Moore was only able to convince seven of his colleagues to leave Shockley, and the writer had not yet joined the “traitors.” These seven individuals needed capital to start a new business. One of them, Eugene Kleiner, wrote a letter to his father’s stockbroker at the highly reputable company Hayden, Stone & Co on Wall Street, stating that “we believe we can enter the semiconductor field with a new company within three months.”

The letter caught the attention of Arthur Rock, a thirty-three-year-old analyst who had achieved great success through risky investments since his days at Harvard Business School. Rock convinced his boss, Bud Coyle, that a trip to San Francisco to meet with the traitors was worthwhile.

When Rock and Coyle met with the seven individuals at the Clift Hotel in San Francisco, they realized that something was missing; the group needed a leader. So, they asked them to convince the writer, who was hesitant to join their group due to his sense of commitment to Shockley, to join them. Moore eventually convinced the writer to attend the next meeting with them. Upon seeing the writer, Rock immediately realized that he had the charisma and influence necessary to lead the group. Thus, at that very meeting, all eight individuals, including the writer, agreed to leave Shockley and form a new company together.

In those days, raising capital for a completely independent company startup was really difficult, because the idea of initial investment for startups had not yet been established. Arthur Rock, eleven years later, still nurtured the idea of risky investment to help Moore and Noyce start their new business. He said, “Money was on the East Coast, but exciting companies were in California; well, I decided to come west and connect these two.”

Rock prepared a list of 35 companies that might be willing to invest and contacted them as soon as he arrived in New York. But according to Rock, “None of them were willing to invest in another company because they felt their employees would object. I was involved in this issue for a few months and was getting discouraged until someone suggested Sherman Fairchild to me.”

It was as if the writer and editor’s familiarity with Sherman Fairchild was written in the stars! Fairchild was an inventor, entrepreneur, and the largest shareholder in IBM, whose father was one of its founders. He invented the first synchronized camera shutter with flash in his first year at Harvard. After that, he went on to develop aerial photography, radar cameras, specialized planes, methods for lighting tennis courts, music recording, lithography for newspaper printing, color engraving machines, and wind-resistant matches.

Fairchild, who founded 70 different companies throughout his life, easily and without any opposition, agreed to put $1.5 million (equivalent to $16 million today) in the middle of starting a new company; about twice what these eight people needed. But, there was a condition attached – if Sherman’s investment proved successful, he would be permitted to acquire the entire company for around $3 million.”

Thus, Moore and seven others founded their new business in 1957 on the outskirts of Palo Alto, right down the street from where their previous company was located. As the situation grew more dire for Shockley Semiconductor, things were going very well for these eight traitors. They launched Fairchild Semiconductor with a massive investment from Sherman Fairchild, at just the time when demand for transistors for pocket radios by Pat Haggerty’s Texas Instruments was soaring and on the verge of another astronomical increase. On October 4, 1957, just three days after the founding of Fairchild Semiconductor, the Russians launched the Sputnik satellite, and the space race with the United States began.

The non-military space program, alongside the military program for building ballistic missiles, greatly increased the demand for computers and transistors and caused the development of these two technologies to be intertwined. As computers had to be made small enough to fit them in the cone-shaped head of a missile, finding a way to place hundreds and then thousands of transistors in small devices became essential.

Two years after the founding of Fairchild Semiconductor, Sherman exercised his right to take over the company and, by paying $300,000 each to the eight founders, made them wealthy (about $3 million today per person).

These eight people remained in the company, but they no longer had any control or responsibility for its success or failure. The writer was promoted from the director to the deputy of the parent company and was highly respected by Fairchild; but everyone knew that the big decisions were now being made elsewhere.

By the 1960s, the main team members had lost their patience and one by one left Fairchild Semiconductor to start their own businesses. Fairchild was like a sycamore tree with many bald seeds that fell with the wind, grew right there, and turned into new seedlings that they called “Fairchildren”; startups like Intel and AMD and 30 other new companies that helped propel Silicon Valley.

Finally, in 1967, the era of Fairchild Semiconductor came to an end as well when Charlie Sporck, the company’s brilliant and charismatic leader, launched National Semiconductor in direct competition with Fairchild and brought a slew of his old colleagues to his new company. This dealt a severe blow to Fairchild, and Moore and Noyce could no longer do anything to stop the exodus. A year later, the two were the only remaining members of the “traitorous eight” still working at Fairchild Semiconductor, but their departure was imminent.

When a local newspaper asked Moore in 1968 why he and Noyce had finally decided to leave Fairchild and start their own business, he said they wanted to experience the excitement of working at a small company with remarkable growth again.

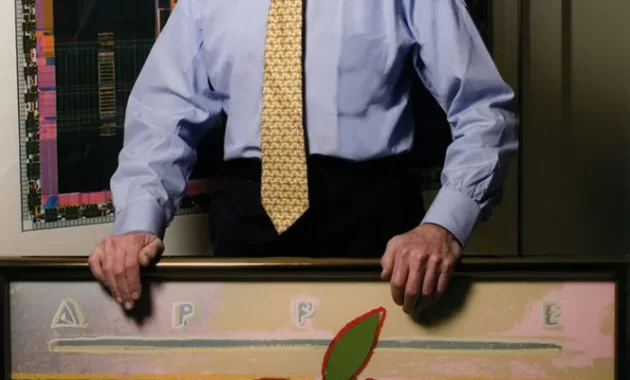

The Birth of Intel

The momentous conversation that led to the birth of Intel occurred during a sunny weekend afternoon while Robert Noyce was mowing the lawn of his house. Gordon Moore, who was the head of research and development at Fairchild Semiconductor, was tasked with developing the new company’s product line. Noyce, who had led negotiations with Sherman Fairchild eleven years earlier to create the company they were now leaving, was responsible for raising capital for the new company.”

Noyce needed only a phone call to raise capital. A decade ago, the deal with Fairchild was made by Arthur Rock, a New York investor, and since then, Rock’s life had been intertwined with the founders of Fairchild. He moved to California and launched a new investment bank in San Francisco specializing in financing new companies (today, we know this business as “venture capital”; a term coined by Rock himself).

Out of loyalty to Sherman Fairchild, Rock did not want to have a role in his company’s collapse, but he had previously helped two of the remaining six founders to start their own business, and Robert Noyce was his best friend among them.

Immediately after calling Noyce, Rock called 15 investors and received 15 positive responses. Of course, Rock’s goal was not just to raise capital for Noyce and Moore, as with the experience and influence of these two, all the capital could be doubled. Instead, Rock wanted to find investors who could provide their knowledge and expertise to help Noyce and Moore start their new business.

The new company was named only a few weeks later. Noyce and Moore initially used the name “NM Electronics,” but both believed it was too old-fashioned. After reviewing several different names, Moore eventually chose the name “Integrated Electronics,” and then Noyce abbreviated it to “Intel.” Arthur Rock, who had doubled the company’s startup capital and now served as the first chairman of Intel’s board of directors, had no problem with this naming. Thus, on July 16, 1968, Intel was established in Palo Alto, the wealthiest neighborhood in San Francisco, and in the northernmost part of it.

“However, both Noyce and Moore realized very late that there was another company called Intelco before them. But at that time, Intel’s name was everywhere, and the simplest way to prevent any complaints was to pay $15,000 to the hotel company Intelco for the right to use the Intel name.

Two weeks later, in August 1968, a local Times newspaper contacted Gordon Moore for an interview about the new company. The interview text included the addresses of Moore’s and Noyce’s homes, and within a few days, a flood of calls, resumes, and letters from engineers looking to work at Intel were directed towards them. Finding experienced employees willing to work at a startup is really difficult, but Noyce had no trouble attracting experienced talent due to his achievements in integrated circuits and Moore due to his outstanding record at Fairchild.

When in the early days of Intel’s establishment, the local newspaper asked Moore what devices they were going to work on, Moore’s response was very vague and ambiguous. He said, “We are particularly interested in producing products that no manufacturers have ever introduced to the market.”

When he was asked to explain more, Moore only added that the new company would avoid any direct contact with the government and that its focus would be on the industrial sector rather than producing consumer products. Moore believed that there was no need to give potential competitors any extra information, even though it was outdated.

But behind this ambiguity, Noyce and Moore knew exactly where their new business was heading. They intended to produce memory chips. Throughout the United States, companies were using magnetic core memory to manage accounting systems, medical records, and employee payments. These systems were slow and expensive, and they were desperate for a better solution. The new company’s products could solve this problem.”

The cheapest type of computer memory at that time used “magnetic cores”; magnetic components shaped like donuts made of ferrite material that stored information as a series of ones and zeroes depending on their magnetic orientation. If there was a way to integrate memory cells with circuits that the inventor had devised, computer memories could become much more compact and faster.

As soon as a computer company began using integrated circuit memory, other companies were certainly eager to follow suit. In the next step, the significant increase in production and cost reduction led to the complete replacement of magnetic core memories with new semiconductor memories. The demand market for this type of memory was millions of units per year. And so it was that with the birth of Intel and the production of the first memory chips and microprocessors, the foundation of the modern world was laid.

With the help of silicon microchips that are actually the brain of the computer, Intel enabled American manufacturers in the mid-1980s to outperform their powerful Japanese rivals in the vast field of computer data processing. Until the 1990s, Intel placed its microchips in 80% of the computers made worldwide and became the most successful semiconductor company in history.

Moore’s Law

Gordon Moore spoke humbly in an interview in 1997 about the birth of what later became known as Moore’s Law. “Back then, integrated circuits had just set foot on the field. The most complex chip was still a laboratory model in Fairchild, which had about 60 components including transistors and resistors. I was writing an article for the 35th anniversary of Electronics magazine and was asked to predict the future of semiconductors for the next 10 years. I was sure that integrated circuits would be very important because their impact on cost reduction could be seen. So, I looked back to the past. I took 1959, when there was only one transistor, as year zero. We had reached 64 transistors six years later. I said, ‘Oh, the number of transistors doubles every year.’ Then I said, ‘Well, this trend will continue for the next ten years,’ and we really followed this trend with the same precision. Of course, another person named it Moore’s Law; I think it was Carver Mead from Caltech; he had a habit of doing things like that.”

The reason why everything was getting smaller, cheaper, faster, and more powerful every year was that two intertwined industries, the computer industry and the semiconductor industry, were growing together. It was exactly like what happened half a century ago with the oil industry and the automotive industry.

The article that Moor wrote for the April 1965 issue of Electronics magazine, which was supposed to predict the future of the market, was titled “Putting More Components on Integrated Circuits”.

Moor began his article with a brief look into the digital future. He wrote, “Integrated circuits will lead to such wonders as home computers, or at least terminals connected to a central computer, automatic controls for automobiles and personal portable communications equipment.”

Moor then made another prediction that put his name on everyone’s lips. He wrote that “the complexity for minimum component costs has increased at a rate of roughly a factor of two per year… Certainly over the short term this rate can be expected to continue, if not to increase. Over the longer term, the rate of increase is a bit more uncertain, although there is no reason to believe it will not remain nearly constant for at least 10 years.”

In simpler terms, Moor’s point in this article was that the number of transistors that could be placed on a chip for the minimum cost doubled every year, and he expected this trend to continue in the same way for at least the next ten years.

In 1975, ten years after this prediction, Moore’s Law was proven correct. Moore then revised the law by halving the rate of improvement and said that the number of future transistors on a chip “will double every two years, rather than every year.”

One of Moore’s colleagues, David House, who realized that the processing speed of components had also increased over time, made other modifications to this law that are sometimes used. He said that due to the increase in power as well as the number of transistors on a smaller chip, the “performance” of the chip doubles every eighteen months.

Moore’s Law was more than just a simple prediction; in fact, it was a roadmap for an industry that somewhat covered this prediction. The first true example of the implementation of Moore’s Law occurred in 1964 when Moore was shaping his law. Robert Noyce concluded that Fairchild would sell its simplest chips for less than their production cost; a strategy that Moore called “Robert’s Charity to the Half-World Industry.”

Noyce knew that low prices would encourage manufacturers to include chips in their new products. He also knew that low chip prices would increase demand, mass production, and economies of scale (cost reduction advantage due to increased production volume), all of which would make Moore’s Law a reality.

In fact, to better understand Moore’s Law, it should be viewed not as a physical law, but as a law of economics and corporate motivation. Processing power doubles because consumers expect it to and new applications are found for the added power. Consumer demand, in turn, forces companies to find new ways to keep up with their expectations. For example, in 2011, market pressure led to innovations such as 3D transistors and improvements in manufacturing processes to the extent that in 2021, IBM was able to produce a chip in a size of just 2 nanometers.

Do you think if Moore’s Law was true for all industries, what would the world look like now?

In the 1960s, when Moore was just starting out in electronics, each silicon transistor was sold for $150; but later, with the advancements that Moore and his colleagues made, more than 100 million transistors could be bought for $10. Moore had once said that if cars had progressed as quickly as computers, you could drive 100,000 miles on one gallon of gas, and buying a Rolls Royce would be cheaper than parking it.

Is Moore’s Law dead?

Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, announced that “Moore’s Law is dead” when the RTX 40 graphics cards were released in 2022, which faced a significant increase in prices. However, many experts believe that Moore’s Law is still alive, only its speed has slowed down. The performance of single-chip processors has increased by about 30% per year on average over the past five years, while in the late 1990s, the rate of performance increase for processors was very significant, and they were doubling their performance every two years.

In numerous interviews, Moore has said that the end of Moore’s Law is inevitable. In an interview with Techworld magazine in 2005, he said that the law “can’t go on forever. The nature of exponential trends is that they eventually come to a disastrous end.”

Gordon Moore’s biggest dream

When asked in an interview in 1997 what he thought we should do with the powerful chips that would exist 15 years in the future, Moore gave an interesting answer:

“The thing I always come back to is advanced voice recognition technology. I really think that a computer that you can talk to…that can understand your words, not just the words but the meaning behind them…will turn the computer world upside down, and I think it’s a goal worth pursuing.”

“This is what is supposed to put computers and computing in the hands of the 85 percent of the people who don’t participate in the field today. And you know it takes processing power and memory to do it, but I really think it’s worth it.”

“You should be able to ask your computer to search the Internet for you, gather the information you’re looking for and give it to you; like when I ask my technical assistant to go out and find something about this or that, and then put it into the computer. I think it’s fantastic and entirely doable…if not by 2010, by 2050 or so. They’re entirely doable and the more processing power and memory you have, the more you can do with them. On the other hand, computers will become powerful tools for communication.”

“I think in the future, computers will be used more for communication than for their computing power. I think computers will become companions, and we will be talking to them.”